Can You Beat the Market?

Economist Justin Wolfers, who has a PhD from Harvard, published an article in the New York Times on September 30th called “Debate Night Message: The Markets are Afraid of Donald Trump”. I quote the article’s first two sentences:

Political leaning aside, let’s breakdown this argument. The article proceeds to tell us that “decoding markets is no easy task”, the process used “close analysis of financial markets during Monday’s debate” and cited specific examples of what Trump said versus how the market on a whole reacted to it. Wolfers also cited his conjoined research with two other well-respected economists at venerated universities. This research back-tested how the markets have responded to the presidential elections dating back to the 1880s.

Wolfers is obviously intelligent. He has access to large amounts of data. He’s not in a stuffy suit on Wall Street, but rather an academic at the University of Michigan, shaping young minds. He did his research and drew his conclusions. And he couldn’t have been more wrong. While there may still be a chance of a broader economic turndown (Wolfers did not give an approximate date of this), the S&P 500 has increased by 6.71% (November 8th, 2016 to January 13th, 2017). Wolfers’s prediction is a couple of standard deviations off from the right number. But what if Wolfers is actually right? If Hillary had won, it is possible that the market would be up 17-19% and other factors outweighed the negativity of a Trump win. This is the challenge with predicting markets: even after the fact, we don’t know if we were right or if the outcome occurred for reasons beyond our predicting capabilities.

Finance is complex, with many moving parts and many people around the world making financial decisions every minute of every day. These decisions may be based on a prediction like that of Justin Wolfers or by a pension fund manager who is rebalancing a large portion of the company’s retirement portfolio. Conversely, the action to buy or sell an investment may have nothing to do with the investment itself – for instance, a wealthy investor may need to sell a portion of his assets to have cash for a large purchase. Another big investor may have cash that he would like to store in short-term bonds, before making additional investment decisions. The combined result of these financial decisions dictate the price of the market on any given day.

Sometimes you or I are one of these people, making financial decisions that influence the market, albeit insignificantly. Part of making such financial decisions is choosing how to invest. On one end of the spectrum you can “buy the market”, which is a diversified set of publicly traded companies where you receive the “average” return. On the other end of the spectrum is picking and choosing a few individual stocks and timing when to buy or sell them. A common assumption is that the latter allows you to avoid big drops in the market, like in 2008. We find a sense of security in choosing our own investments so that we may better control our outcome of returns.

Somewhere in between buying the market and picking individual stocks is buying a mutual fund with a manager who buys and sells companies for you. This is a popular choice because investors can rely on the skill of the manager to not only choose good companies, but also choose the time to buy and sell them. All the investor must do is decide which manager and when to buy the fund. Easy-peasy, right?

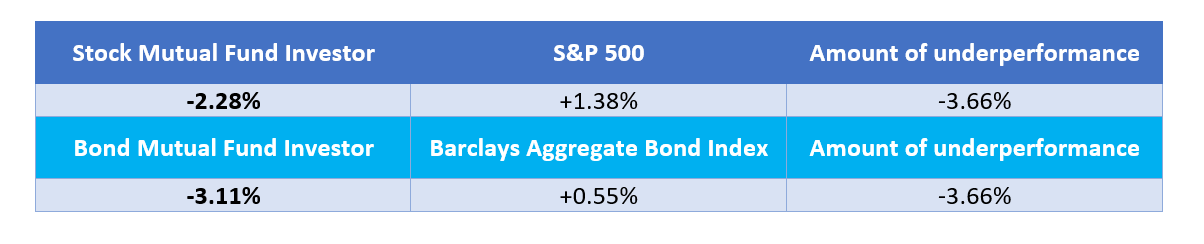

Not quite - the DALBAR study looks at how investors fair when they pick mutual funds. The study clearly shows that investors have significant underperformance over time. While this study only researches individual investor performance versus the benchmarks of the mutual funds he or she holds, it is a good proxy for investor behavior on a whole, whether it be picking stocks or mutual funds.

In 2015, the average stock mutual fund investor underperformed the S&P 500 by 3.66%. Bond mutual fund investors underperformed the bond market by the same amount.

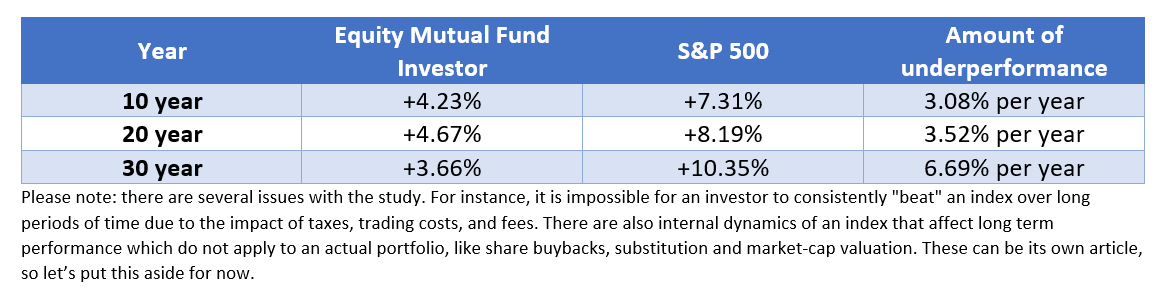

In 2015, the 10, 20 and 30 year annualized returns look even worse:

Why do investors have such significant underperformance? While some of it is accounted for by poor manager performance, which we will discuss later, let’s take a little ownership here! We, as humans, have some bad habits and emotional flaws:

- We tend to think of progress as a straight line rather that its true bumpy form. This often leads to us to assume that a company or manager on the rise will continue to rise.

- We like to complicate things. For example, not only do we want to time the market, but we also want to choose which managers or companies will outperform at any given time.

- We tend to be irrationally optimistic and pessimistic at the worst possible times. Instead of successfully buying the market or companies at low prices and selling them at high prices, our emotions compel us to do the opposite. We are much more likely to buy high (fear of missing out) and sell low (fear of losing everything).

- We are attracted to rising prices, incorrectly extrapolating that past price changes will continue to persist in the future. Have you ever seen this disclosure on anything investment related: “Past Performance is NOT Indicative of Future Results”? It’s there because it’s true.

- We are overconfident in our investing skills. This is because we have been successful in other areas of our lives, thereby earning the funds we have saved for investment. Accepting the market return goes against this inclination to use our smarts to outperform.

- We go with the herd because there is comfort in being part of a group. We are social creatures and being a contrarian is lonely.

- We fear making poor decisions in general. We don’t like to feel like we made a bad investment decision. This may cause us to wait on the sidelines with uninvested funds out of fear of investing at the exact wrong time. Unsuccessful decisions often lead to endless ruminations over what we coulda, shoulda, woulda done.

If human beings have emotional flaws – can it be possible that professional investors are immune from this? It turns out, investment managers are not great at beating the market either. This is true for mutual fund managers, pension funds, hedge funds and you guessed it financial advisers and planners. After all, we are only human!

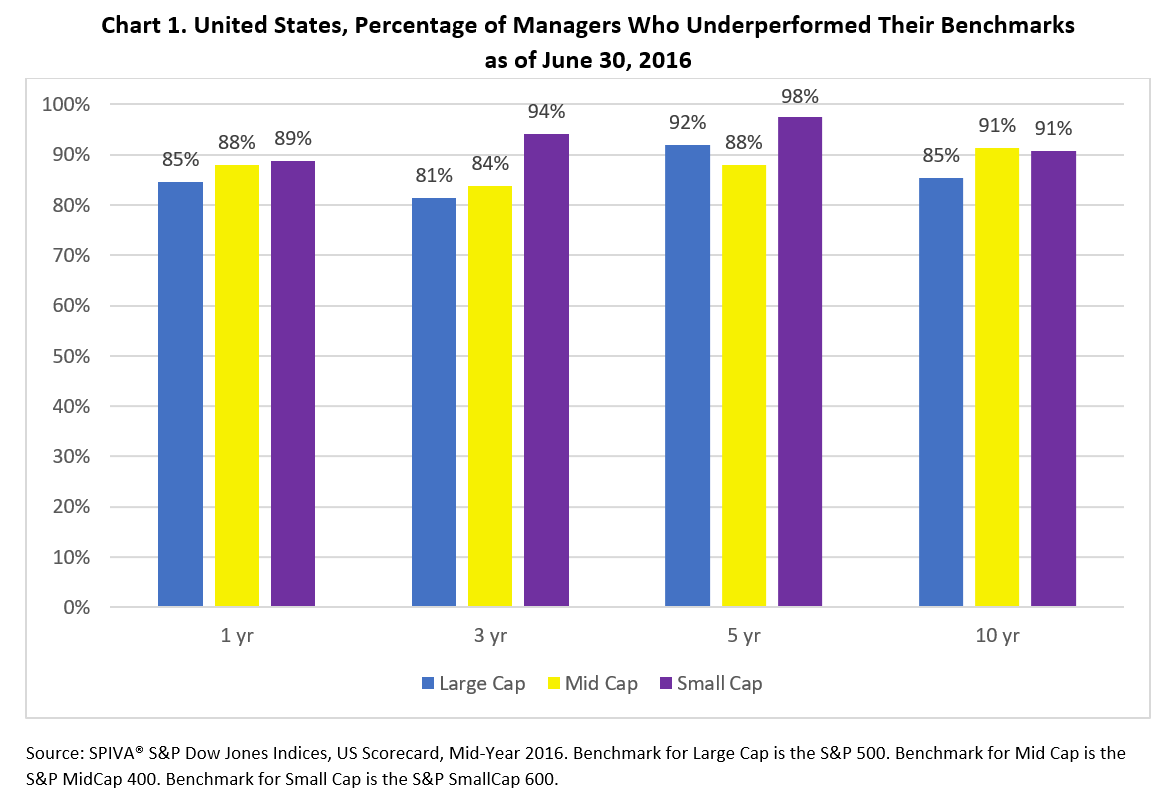

A study done by S&P Down Jones shows that active mutual fund investors (i.e. the mutual funds that are not indices) fail to beat their benchmarks:

As we can see from above, mutual fund managers do not consistently beat their benchmarks.

For those of you who think the US markets are more accurately priced than the rest of the world, look at both international and emerging markets:

If 80% of fund managers around the globe, with large, highly paid teams of people looking at hundreds of data points every single day can’t beat the market, why would you or I doing a small amount of research alone in the dark presume to do any better?

You may at this point be saying to yourself, “yeah but, those stuffy Wall Street people at their desks don’t know anything about the real world. I work in [insert your professional industry here]. I know much more than any of these folks would about this part of the market”. You may even be saying, “I don’t care what other people do or don’t know, I can do it better.”

Economist John Kenneth Galbraith once said, “We have two classes of forecasters: those who don’t know and those who don’t know they don’t know.” I follow that up by asking you the following:

- Why do you think what you know isn’t already priced in to the market or company you wish to buy or sell?

- Why do you think what you know matters more than other factors in determining the price?

- In addition to the above, why do you also think you can predict how other people view this information only you have when it comes to light?

All of this tells us that markets are unpredictable. Investment managers get it wrong, academics get it wrong, the Jim Cramers of the world get it wrong and most importantly, we, the individual investor, get it wrong. We have very little predictive power. While the price reflected at any given time may not be the true value of the market or company in question, it does not mean we will ascertain the correct value or that the “correct value” will ever come to fruition.

The market doesn’t wait for you while you complete your research, weigh the pros and cons, and make an investment decision. The market doesn’t care if you do lots of research or no research at all. Most importantly, the market doesn’t care how high the stakes are: your entire financial future depends on your decisions.

With high stakes comes increased responsibility, which can be time-consuming and both intellectually and emotionally taxing. It is difficult for us as investors to effectively create our own financial plan and implement it perfectly. This difficulty increases exponentially as we account for small things like taxes, rebalancing, trading costs and fees, and big things like major life events that necessitate an overall change in how we invest. And while it is certainly self-serving for me to say – seek the help of a financial planner to navigate your personal finances, I say this because it is true. With the help of a competent professional, you can work these problems out together. Let your financial planner experience the time-drain, and the mental and emotional effects of managing your complete financial picture, while you sleep, have date-night with your spouse, or play with your kids on the weekends!

When it comes to investing, we can control the following:

- Our savings rate

- The percentage we invest in stocks, bonds, real estate and cash, generally dictated by our risk tolerance and the amount of cash (liquidity) we need

- The amount of insurance we need to protect ourselves from knowable risks

- The types of accounts we can put our investments in (Taxable, tax-deferred, tax-free)

- Our estate plan – who receives our money and how they receive it

Everything else is just a waste of time.

If you enjoy investing in individual companies or timing the market, consider it a hobby. The amount you choose is the amount that you are willing to completely lose, as though you are going to Vegas. Remind yourself that it is a game that you enjoy, rather than a plan to sustain your financial needs throughout your life and in retirement.